Zürich: Trix and Robert Haussmann are known for putting a cape on the United Nations Building in New York (in a collage, at least), but how do they go about dressing their own home in Zürich, Switzerland? Trix and Robert Haussmann, both architects, have lived close to the Lake of Zürich for 45 years. Opposing the widespread tendency of architects to tear down buildings in order to build new ones, the couple has been layering layer upon layer of their own design upon their typical working class house, initially used by the conductors of Zürich’s very first tram.

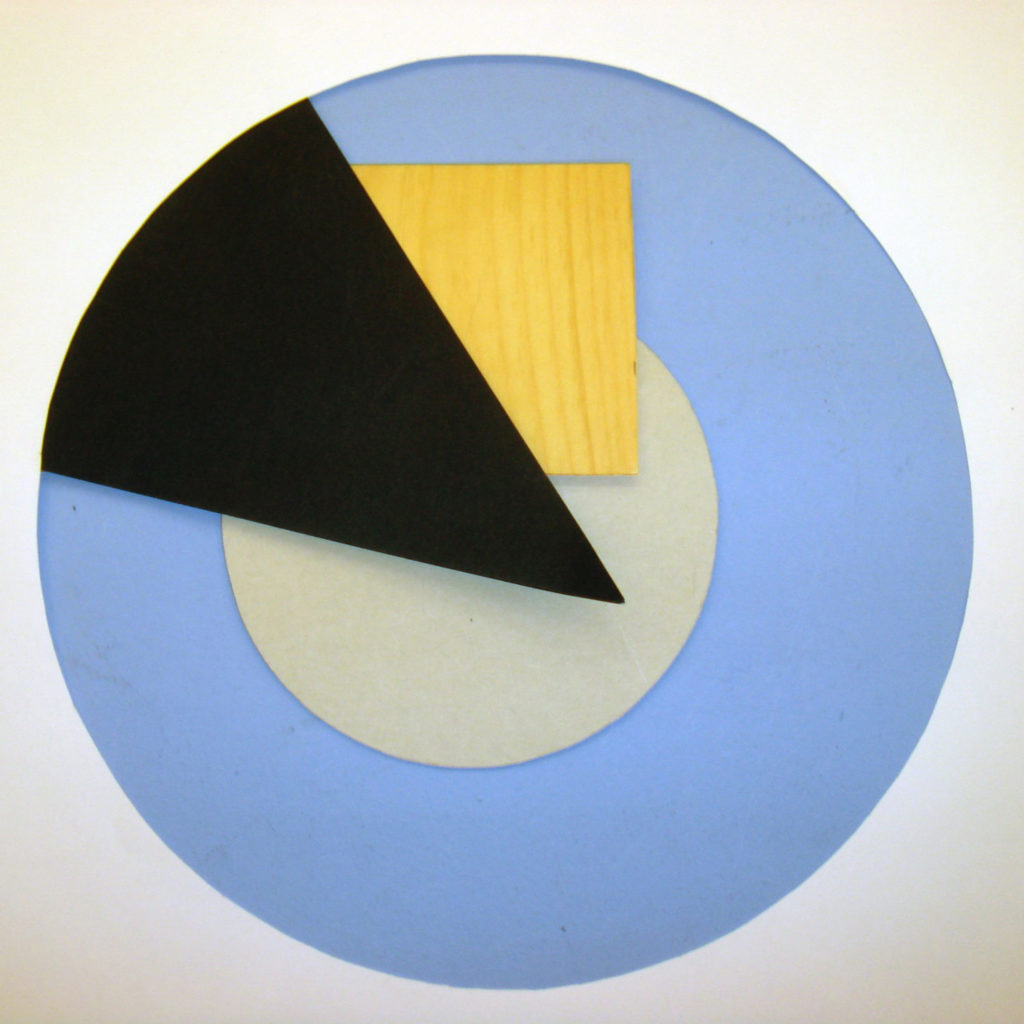

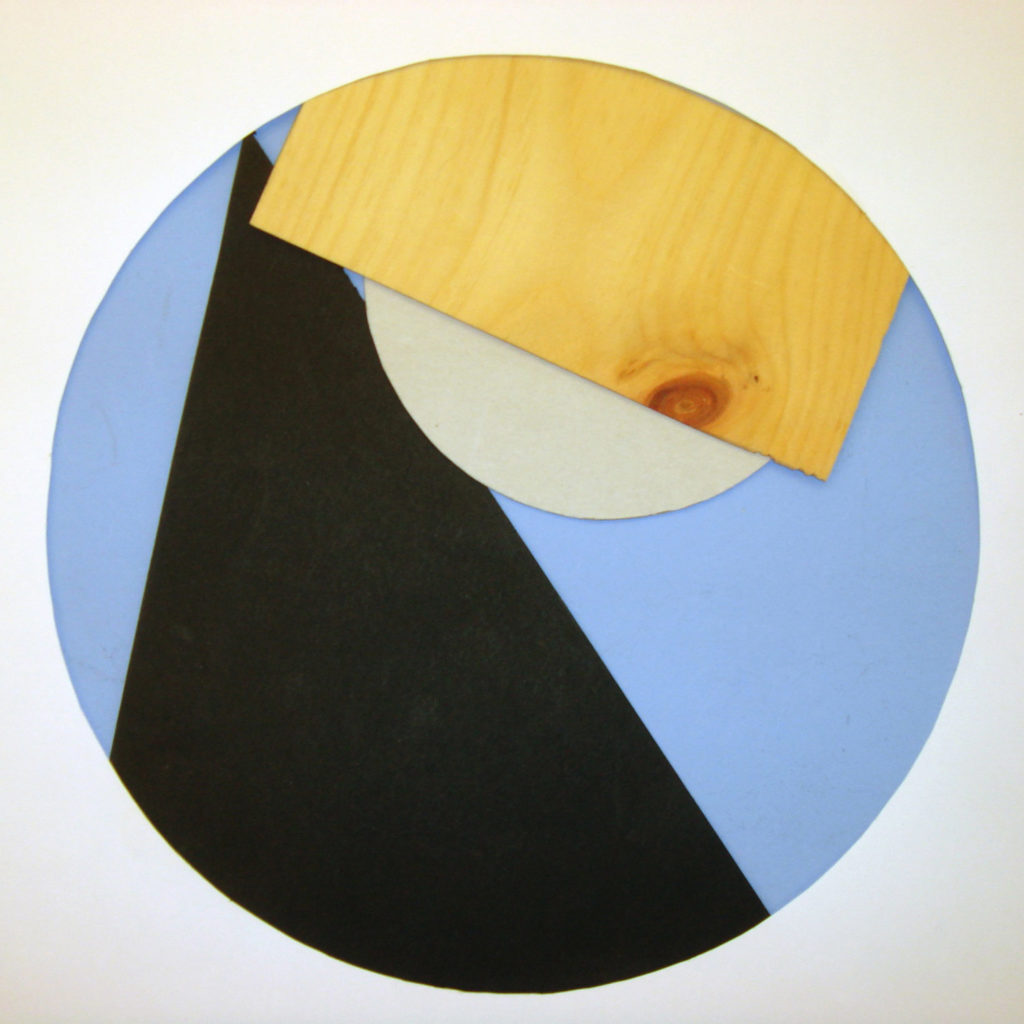

Since then, the house has become a place for them to live in, an office, an impromptu museum, and a mirror cabinet. After I arrive we play a quick game inspired by Jean Arp’s loi du hasard, in which the visitor to the house throws a cut-out circle, triangle, and square onto a white sheet of paper while Trix Haussmann takes pictures of the impromptu compositions. Then we delve into conversation about the art of collecting paintings that almost eat you, which of the two does the cooking, who designs the kitchens, and what it means to the Haussmanns when they say that they have found many ‘little bears’ in their life.

But now that there are many Swiss artists in your collection that you know personally, you must have a story to tell for each work of art in the house?

Robert: We do, yes. These Friedrich Kuhns, for example, when I bought them from Friedrich I kind of functioned like a bank for him. Whenever he needed 100 francs he would come to our house to get them until I had paid off the painting in full. After that the next 100 franc would serve as a pre-payment for the next painting, that I was going to buy anyway.

Trix: Kuhn expressly did not want to receive all the money for a painting at once.

Walking through your house reminds me of a film I saw recently, Garden State by Zach Braff. There’s a doctor that has so many diplomas that he has to hang the last one on the ceiling. Have you considered hanging your art on the ceiling as well? Every other piece of wall seems to be covered…

Robert: Maybe the floor would be a better option. It’s interesting that a lot of people seem to have their diploma in the toilet. What you do not take too seriously, you put in the toilet.

At least you have time to read there. Although, I didn’t see any diplomas here, not even in the toilet. How do you go about hanging new works?

Trix: We have tried different principles. First we wanted to have the same frames for all paintings. But of course the artists didn’t adhere to our frame size! So now it’s more a matter of gut feeling. Robert usually goes about it very intuitively—

Robert: All I need is a bottle of champagne to hang a new painting. I still find it extremely difficult to describe why a painting looks good next to another one, or why not. We actually met for the first time while visiting an artist friend we both had in common, the sculptor, Bernhard Luginbühl, who is known for his big iron works. The first works that we bought together were drawings by Luginbühl.

Trix: We both brought some works with us when we moved in to this house, 45 years ago. We shared a certain taste from the start. We both seem to be interested in the stranger works of artists. Not the likeable ones, but the ones that show the true character of an artist. The ones that are not really meant to be looked at, or to be sold, but where something just had to get out. Like this monstrous rose by a friend of ours—it almost seems to eat you!

Robert: How we like it, but it’s not likeable.

I’ve seen a lot of paintings dealing with optical illusions, like the ones you use in your own design work.

Trix: We mainly buy works with ideas that we did not have ourselves—

Robert: Like this piece by Hugo Suter with the milk glass. This is really an idea that we never thought of. If you look at it from the front, it looks like a rose out of focus. But if you go behind it, you realise that the rose has been made up of used bottles of cleaning liquid. If we had all the money in the world, we would of course have many Magrittes and de Chiricos on top of all that.

Have you ever been asked by an institution to exhibit your collection?

Robert: We’ve never done it. It could result in an interesting double portrait—or even a double psychogram—in an unusual medium. This work by Alfred Hofkunst, by the way, it’s up there because it is exactly the same width as the painting below. It’s a true to scale drawing of a perfectly normal scale of two metres in length. When I saw it, I knew that this was a perfect gift for my architect wife. However, Hofkunst made one mistake, it’s 200 centimetres, but not exactly in the right order.

Trix: This is a kind of coincidence that we often see in our art collection, but that we also find useful in our design work. Robert has been working with the concept of coincidence a lot.

Robert: I firmly believe in Jean Arp’s loi du hasard and share his conviction that art and design can develop out of coincidences. In German the word ‘coincidence’ is ‘Zufall’. It’s what ‘falls onto you’, so to speak.

Is that why you ask every visitor to play a game where he or she lets cut-outs of three different forms fall onto a piece of paper whilst you take photo of the coincidental result?

Trix: That’s really just a game that we are interested in right now.

Robert: And it shouldn’t be taken too seriously. But of course, it is a very conscious construct for playing with coincidence. And the results are always interesting and beautiful in some way!

So it’s coincidence that follows certain rules.

Robert: We have been influenced a great deal by literature. By Oulipo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle) writers like Georges Perec, Italo Calvino, and Umberto Eco, for example. They show how to play with coincidence and how to break rules.

Trix: And how you can’t break rules if you haven’t constructed them first.

And what rules apply to your house? Which, by the way, also seems to be kind of a double portrait as a whole, doesn’t it?

Trix: It is maybe more a room for experiments. For example, we wanted to find out how paintings can be hung on coloured walls, so we chose a different colour for each room of the house. Grey for the staircase, and blue, yellow, or green for the rooms. It took us about five years to complete this concept and to establish the rules that apply to it.

Robert: There was no real rush. Of course this colour concept does not apply to all types of architecture. In a house by Richard Neutra, with its flowing rooms, you couldn’t colour one individual room. But in this house, with little boxes as rooms, it makes sense. You must know that I was a student of Johannes Itten, and I got to know his colour theory very well.

Trix: For most of our commissions, you decided on the colours. I always said I was colourblind. I was always so annoyed by the common assumption that women always take care of colours and textiles.

Little bears inside things

Interview by Daniel Morgenthaler

Photography by Lukas Wassmann

Leave A Comment